ADVERTISING AS IMPRESSIONISM

September 10, 2024

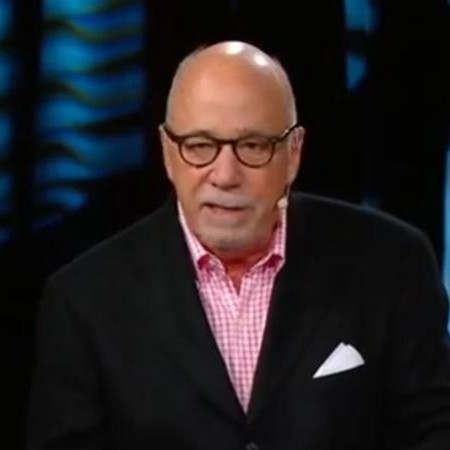

By Bob Hoffman

By Bob Hoffman

I would like to present an alternative theory of how advertising works, and how we should think about the creation of advertising.

I believe the advertising industry has an incomplete theory of how advertising affects people. Traditionally we have described the elements of advertising impact as a blend of logic and emotion.

The case for “logic” suggests that consumer behavior is mostly rational. This idea (as first argued by Adam Smith) asserts that markets are rational and people behave rationally. They do not throw their money away on stupid crap. There is a lot of persuasive evidence for this model. A good example is in retailing. Retailers know that they can stimulate sales by lowering prices, offering discounts, and utilizing other types of promotional activities. This is clear evidence for a logical basis for some consumer behavior.

The case for emotion asserts that consumer behavior is largely non-rational. The basis for this theory, brilliantly demonstrated by Daniel Kahneman, holds that people are not fully aware of their motivations and are often ruled by emotions. The evidence for this model is equally persuasive. I have previously written about the Toyota Corolla that was the exact same vehicle as the Chevy Geo Prism, cost $1,500 more, yet outsold it 3 to 1.

In the prevalent theory of how advertising works there is presumably some balance of logic and emotion that will be best suited for purpose. In some cases a highly logical approach is preferable. In other cases a more emotional approach is best. This binary logic/emotion continuum is a false dichotomy that ignores a powerful and equally important factor. We’ll get to that in a minute.

But first, let’s talk about subatomic physics.

Quantum physics gives us a useful, if imperfect, analogy to what I am proposing. Before quantum theory, subatomic thingies were described as either particles or waves. Quantum theory taught us that under some circumstances a thingie might behave as a particle and under other circumstances it might behave as a wave. It provided a liquidity between particles and waves. You could choose to call it a particle or call it a wave, but whatever a human decided to call it was irrelevant. In reality it was still an imprecise, fluid sub-atomic thingie – sometimes a particle and sometimes a wave.

Einstein also helped us understand hidden equivalencies. His famous equation E=mc2 taught us that mass and energy, which seemed obviously to be two different things, were actually two manifestations of the same thing. Depending on its energy state, it could appear as mass, or it could appear as energy. Underneath it all, it was the same stuff.

I believe “impressionism theory” can give us a similar “liquid” insight into how advertising works.

Consumers are not logic machines, nor are they puppy dogs. Our traditional belief that logic and emotion are two different and separate things is insufficient. Our belief that advertising’s effect on consumers is some amalgam of logic and emotion is also insufficient.

Let’s look at an example.

Dave Trott has written about an incident in which Charles Saatchi was searching for an idea for a poster to convince people to cover their food so flies wouldn’t spread germs to it. Saatchi was rifling through material on the subject when he came across some old leaflets. According to Trott…

One of the leaflets had this written in it:

“This is what happens when a fly lands on your food.

Flies can’t eat solid food, so to soften it up they vomit on it.

Then they stamp the vomit in until it’s a liquid (usually stamping in a few germs for good measure).

Then when it’s good and runny they suck it all back up again, probably dropping some excrement at the same time.

And then, when they’ve finished eating, it’s your turn.”

Saatchi said “That’s it, don’t change a word, that’s the poster.’”

This is an excellent example of a logical argument that undoubtedly generates an emotional response. It shows us clearly that logic and emotion are not so distinctly different as we might think. In fact it is highly likely that logical arguments can lead to emotional reactions, and vice versa. You might choose to call a reaction to this story logical or you might choose to call it emotional. But underlying whatever you call it is one undeniable fact – it created a strong impression. The impression was the primary asset that was delivered.

The processing that goes into a buying decision is imprecise. We have chosen to describe it as some combination of logic and emotion. While both may be relevant, this description is not comprehensive. The ultimate product of advertising may sometimes be a logical conclusion or it may sometimes be an emotional feeling, but it is always an impression.

Advertising creates an impression whether you intend it to or not. That impression may be strong and positive, or weak and meaningless. The power of that impression is related to the skill with which it is delivered.

Both the “logic” model and the “emotion” model, while intellectually attractive, have unpleasant side effects. The idea that advertising must present logical ‘benefits’ has lead to a catalog of truly horrifying ads based on what I refer to as the “court case” framework in which ‘our-brand-is-better-than-their-brand-because’ is the underlying structure. The idea that advertising must engender emotion to be effective has also lead to painfully awful ads featuring instantly forgettable vignettes of Grandpa and Timmy fishing, or birthday surprises at the old folks home.

But a theory of advertising based on the strength of impressions leads us away from those traps. It leads us to a model of advertising in which the power of the delivery of the impression takes precedence over the false dichotomy of logic and emotion.

One of the primary drivers of impressionism in advertising is aesthetics. Some might call it entertainment value, or subjective appeal, or creativity. Aesthetics create a liquidity between logic and emotion. Aesthetic elements of advertising may include design, language, production quality, casting, performance, and music.

The powerful impression that was created by the “fly” example above was driven by the language that was used by the writer. Underlying a logical argument about cleanliness there was aesthetic element that transformed logic into emotion — it created liquidity between logic and emotion — and the result was a powerful impression.

It is my opinion that “impressionism” is at least as important as logic and emotion and is, in fact, how we should think about the effect of advertising.

Aesthetics wash over both logic and emotion and either elevate or diminish the strength of both. Aesthetics are the third leg of the advertising stool and are a powerful driver of the impressionistic nature of advertising.

Neither logic nor emotion is an adequate explanation for the advertising power of a Nike swoosh or a drum-playing gorilla. But impressionism is.

I am obviously not the first to recognize the importance of aesthetics in advertising. But somehow in the literature of our industry we have condensed the effect of advertising into a right-brain/left-brain dichotomy and we have not derived a whole-brain theory. I am choosing to call this whole-brain theory impressionism.

Impressionism theory will be very unpopular with CMOs and MBAs.

These people can point to logical advertising solutions as indicators of their analytic abilities. They can point to emotional solutions as proof of their credentials as sidewalk psychologists. But impressionism, by its very nature, is imprecise. The whole point of impressionism is to be imprecise. Marketers will have a tough time explaining to their egos or to their bosses the value of impressionism.

Marketers prefer precise answers that are wrong to imprecise answers that are right.

Just as “quantum theory” resolved the conundrum of particles and waves in physics, I believe “impressionism theory” may resolve the conundrum of the logic/emotion straightjacket in advertising.

There has been a lot of hand-wringing in the marketing community about the state of creativity in advertising. I may be kidding myself, but I believe “impressionism theory” may open a window to a more undogmatic and supple definition of what constitutes effective advertising.

“Advertising As Impressionism” is excerpted from Bob Hoffman’s forthcoming book “The Three-Word Brief.” Bob is the author of “ADSCAM” and “Advertising For Skeptics”

About Author

Bob is a writer and speaker. He has written six books about advertising, each of which has been an Amazon #1 seller.

He is one of the most sought-after international speakers on advertising and marketing.