Hardships and Wealth Disparities Across Hispanic Groups

September 30, 2022

For the first time, the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) included detailed data on Hispanic groups of different origins.

As the nation recognizes Hispanic Heritage Month, we analyze disparities in well-being and wealth among Hispanic origin groups.

For example, the data show that Hispanics of Cuban origin lived in households with higher net worth than those of Dominican origin.

Each of the detailed Hispanic origin groups, except Colombian (7.3%) and Cuban (8.3%), were more likely than non-Hispanic groups (7.5%) to experience food hardship.

Since 2003, Hispanics have been the largest minority group in the United States. Until the most recent SIPP, public-use files included variables reflecting respondents’ nativity, citizenship status, and whether they were of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin.

But the 2021 SIPP also includes a detailed Hispanic origin measure that specifies whether respondents of Hispanic origin are Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Salvadoran, Dominican, Colombian or some other Spanish, Hispanic or Latino group.

Two topics that are unique to the SIPP are adult well-being, which includes several questions about hardships, and wealth.

Hispanics in the United States

According to the SIPP, in 2021, the Hispanic population made up 18.9% of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population in the United States.

People of Mexican origin were the largest Hispanic group, making up 63.0% of the total U.S. Hispanic population. They were followed by those who identified as Other Hispanic (14.9%) and Puerto Rican (8.8%).

The remaining origin groups made up 4% or less of the Hispanic population: Cuban, Salvadoran, Dominican (3.8%, 3.7% and 3.5% respectively, which do not differ statistically) and Colombian (2.3%).

The sizes of these Hispanic origin groups vary due to a combination of factors, including demographic patterns, such as age structure and birth rates, and migration processes.

Migration is an especially important factor for the Hispanic population that is shaped by historical U.S. socioeconomic and political interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean; the U.S. labor market; social networks spanning across countries; and issues like conflict, political instability, environmental disasters and poverty in origin countries.

Measuring Hardship

Hardship measures indicate whether a household meets basic needs. They’re related to poverty status but capture an overlapping but distinct set of people compared with measures of those in poverty.

This article follows the approach used in past research to generate three household indicators of material hardship experienced during 2020 using SIPP data:

- Food hardship

- Bill-paying hardship

- Housing hardship

A household was considered to have experienced material hardship if it dealt with at least one of the three hardships. The estimates look at individual people living in a household experiencing hardship.

Hardship Outcomes

According to the 2021 SIPP, about 1 in 3 (34.8%) Hispanic and about 1 in 4 (24.3%) non-Hispanic people in the United States lived in a household that experienced material hardship in 2020.

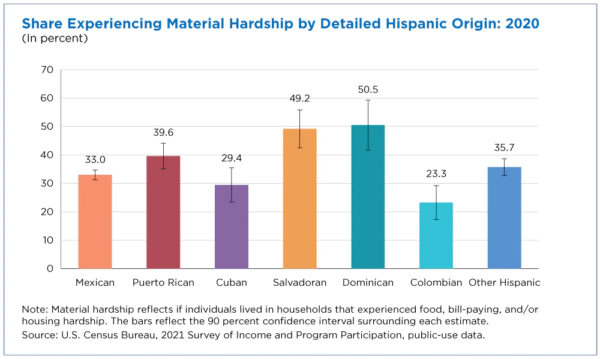

Differences in material hardship were striking among Hispanic origin groups (Figure 1).

Half of those of Dominican (50.5%) and Salvadoran (49.2%) origin experienced material hardship in 2020 (these two groups were not statistically different from each other).

By contrast, those of Colombian origin experienced material hardship least often (23.3%). Estimates of those of Colombian, Cuban (29.4%) and Mexican (33.0%) origin were not statistically different.

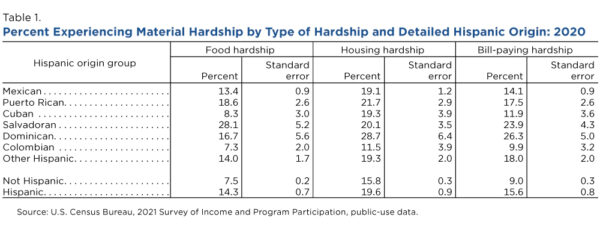

Beyond material hardship as a whole, disparities also existed in specific hardships experienced by Hispanic and non-Hispanic populations and among Hispanic groups (Table 1).

Only 7.5% of the non-Hispanic population experienced food hardship in 2020, compared with 14.3% of all people of Hispanic origin. Each of the detailed Hispanic origin groups, except Colombian (7.3%) and Cuban (8.3%), were more likely than non-Hispanic groups (7.5%) to experience food hardship.

Three in 10 Salvadoran people (28.1%) experienced food hardship, the most of any Hispanic origin group. Estimates of those of Salvadoran, Puerto Rican (18.6%), and Dominican (16.7%) origin were not statistically different from one another.

Meanwhile, housing hardship was experienced by 15.8% of non-Hispanic and 19.6% of Hispanic populations.

Around 3 in 10 people of Dominican origin (28.7%) and 1 in 10 (11.5%) of Columbian origin experienced housing hardship.

About 1 in 10 (9.0%) non-Hispanic people and 1 in 6 (15.6%) Hispanic people experienced hardship paying bills.

Roughly 1 in 4 (26.3%) people of Dominican origin and 1 in 10 (9.9%) of Columbian origin experienced bill-paying hardship.

What factors might help explain these differences?

Prior to 2021, research on detailed Hispanic origin relied on data from other surveys such as the American Community Survey (ACS). That research found that Hispanic origin groups varied in characteristics like educational attainment, types of jobs held, nativity and citizenship status, ability to speak English, living arrangements, geographic location of residence and the race people identify with (access the most recent characteristics by Hispanic origin in this ACS 2021 Table). These differences shape socioeconomic and well-being trajectories and may contribute to some of the hardship-based disparities identified above.

For example, those of Colombian origin tended to be better off socioeconomically than many other Hispanic groups in the United States.

Hispanics of Dominican origin had the highest proportion who reported being Black or multiracial, which may shape their outcomes, since a majority of Latinos said a darker skin color impacts opportunities and shapes daily life in the United States. Many Dominican people also did not speak English very well and the accent with which they speak Spanish is viewed as lower status by other Hispanic groups, which may result in discrimination and limited job opportunities.

The nation’s Salvadoran population also faced significant challenges. Many of those of Salvadoran origin emigrated to escape violence and political instability but most did not receive political asylum or refugee status.

Wealth

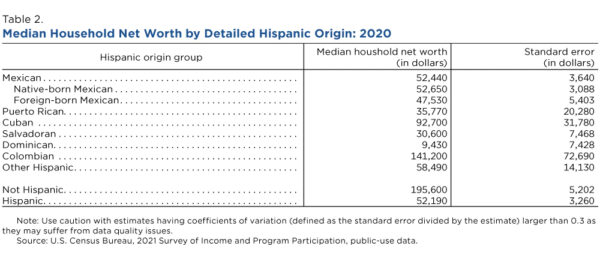

Disparities across Hispanic origin groups extend beyond hardship measures. There were also notable differences in their ability to accumulate wealth, measured by their net worth (Table 2).

Net worth reflects the value of assets owned minus liabilities (debts) owed. In this article, net worth is estimated using information from all household members and shown at the person level to focus on the individual’s experience.

Hispanic people lived in households with a median net worth of $52,190 in 2020 (half lived in a household with net worth at or below and half with a net worth at or above that amount). That was substantially lower than the median household net worth for the population of non-Hispanic individuals ($195,600).

However, this varied among Hispanic groups. For example, while those of Dominican origin lived in households with a median net worth of $9,430 in 2020, median net worth was $92,700 for those of Cuban origin.

Earlier research found that Cubans in the United States were more likely to have at least a bachelor’s degree and to own a home than the Hispanic population as a whole.

In 2020, those of Mexican origin lived in households with a median net worth ($52,440) not statistically different from the median household net worth of the total Hispanic population ($52,190).

Nativity status – born in the United States or abroad – is often associated with different socioeconomic outcomes. In 2017, 33% of the Mexican population – the nation’s largest Hispanic group – was foreign-born. But there was not a statistically significant difference between the 2020 median household net worth of those of Mexican origin born in the United States ($52,650) and those born in another country ($47,350).

While a wide variety of survey-related factors (such as small sample size) could explain the lack of difference between native and foreign-born Mexican people, it is also possible that the data were impacted by descendants of Mexican immigrants from Latin America in the United States who did not report themselves as Hispanic or Latino. Many of these descendants fared better than those who continued to identify as Hispanic, potentially leading to underestimates of the socioeconomic gains across immigrant generations.

Summary

Despite the hardships acutely experienced by some groups, prior research has found that most Latinos still believe the United States provides more opportunity and health care access and is a better place to raise kids than their country of origin/ancestry.

This analysis underscores the value of publishing detailed Hispanic origin data and exemplifies ways it can be used in conjunction with the wide array of topics collected in the SIPP.